Accommodations and Campus Accessibility

Instructor Resources

Introduction

The purpose of this guidebook is to serve as a reference when working with students with accommodations. Every instructor will likely have a student present an accommodation letter at some point during the academic year, so it is important to know how to best support students with accommodations. Disability accommodations are required by federal law to ensure all students have what they need for equal access to college life.

The most important thing to know is that accommodations level the playing field, but do not reduce standards. Disability & Access Resources (DARS) strives to help students meet their disability-related needs and receive accessible learning while also protecting instructors’ academic freedom and upholding institutional standards. An interactive process is required to maintain this balance: Instructors, students, and DARS are all on the same team, working together for the success of the student.

Your Attitude Matters: The Impact of Instructors On Students with Disabilities

Instructors have a strong influence on the experience of all students, but for students with disabilities (SWD), instructor decisions and attitudes can make the difference between having an accessible path to success or an obstructed one.

There is a natural power imbalance in the instructor-student relationship, which can be further complicated when the student discloses a disability and gets an unfavorable response in return due to a lack of knowledge or negative perception. SWD are a vulnerable population, and instructor support is crucial to their success and retention, as instructors are the most impactful figures in a student’s education. Perceived opinions and instructor support are key in students deciding to use or seek out accommodations. Students who feel supported are more likely to seek help, while those whose instructors are unaware or have unfavorable opinions of disability are less likely to get the support they need (Hansen & Dawson, 2020).

Instructor response to disability disclosure sets the tone for the rest of the semester, and possibly the rest of the student’s career (Trammell, 2009; West et al., 2016). Students who have negative experiences with their instructors regarding their disabilities are more likely to withdraw, affecting the retention and degree completion rates of SWD (Becker & Palladino, 2016).

The work you do as instructors and the way you accommodate students with disabilities is important. Your influence affects the trajectory of a student’s education and thus, their life.

*See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic.

The Augustana College Student Population

As we work to provide accessible learning to our students, it is important to understand the population we serve and the most common diagnoses. Below is data that represents Augustana students through Academic and Intake requests from March 2016 to May 2025. This information demonstrates the presence of disability on our campus, and suggests how those disabilities may impact the learning environment. It is important to keep in mind that every student is different and even those with the same diagnosis may have different support needs.

| Number of New Accommodation Requests per Calendar Year | |

|---|---|

| Year | # Students |

| 2017 | 101 |

| 2018 | 131 |

| 2019 | 166 |

| 2020 | 141 |

| 2021 | 159 |

| 2022 | 197 |

| 2023 | 235 |

| 2024 | 205 |

| Total | 1507** |

| Top 10 Diagnoses since 2016* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Diagnosis | # | % of all disclosures |

| 1 | Anxiety | 446 | 30% |

| 2 | Allergies | 389 | 25.8% |

| 3 | ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder) | 296 | 19.6% |

| 4 | Asthma | 274 | 18.2% |

| 5 | Depression | 245 | 16.3% |

| 6 | Migraines | 74 | 5% |

| 7 | PTSD (Post-traumatic Stress Disorder) | 52 | 3.5% |

| 8 | Autism | 52 | 3.5% |

| 9 | Learning Disability | 48 | 3.2% |

| 10 | OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) | 34 | 2.3% |

| Number of Diagnoses per Student*** | |

|---|---|

| # DX | # Students |

| 1 | 839 |

| 2 | 412 |

| 3 | 153 |

| 4 | 55 |

| 5 | 32 |

| 6 | 12 |

| 7 | 0 |

| 8 | 2 |

| 9 | 1 |

| 10 | 1 |

**This data is collected from Academic and Housing Accommodation Request forms since January 2017. It does not include the majority of short-term accommodations or concussions.

***As this is only data from new requests, there may be students who are diagnosed with additional disabilities after their initial intake request or did not disclose all of them initially.

While Asthma and Allergies are frequent diagnoses relevant to housing accommodations, in the academic sphere, Anxiety, ADHD, and Depression represent a large number of students with accommodations. Keeping this in mind when designing courses, selecting materials, or advising can have a positive impact on the success of your students.

The impact of any disability can vary widely, ranging from inconvenient to debilitating. The more disabilities a student has, the more difficult it can be for them to engage in college life. Students with disabilities—especially multiple disabilities—can experience very real barriers that inhibit their success. While in the past, academic accommodations may have been implemented more infrequently, more disabled people are enrolled in college than ever before. This is a trend that is expected to continue.

Legal Framework

All people with disabilities are protected from discrimination based on their disability and are entitled to reasonable accommodations that allow full participation in our programs and activities. These protections stem from state and federal legal requirements, and they operate differently when students are in the K-12 system than in College. These differences can create confusion for students as they enter college. It is important to know the legal framework for providing accommodations so that you understand our legal obligations as a private higher education institution in Illinois.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act (commonly called Section 504) prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities in programs that receive funding from the federal government. Even though Augustana College is a private institution, our participation in the Federal Student Aid Program makes us subject to Section 504.

The passage of Section 504 was a pivotal moment in disability rights history and was the first non-discrimination law for people with disabilities. This law made it possible for people with disabilities to access government-funded buildings and services, including colleges.

The law requires that higher education institutions provide reasonable accommodations to ensure that students with disabilities can participate in and benefit from the educational programs and activities offered. Accommodations that present an undue burden or fundamental alteration to the education program are not required. Section 504 acknowledges that accommodating a student with a disability may also mean providing auxiliary aids and services to ensure effective participation.

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA)

Like Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, the ADA prohibits discrimination against individuals and requires higher education institutions to provide reasonable accommodations to enable full participation in our programs and activities. The ADA has far broader impact for persons with disabilities, prohibiting discrimination in in employment, public services, and places of public use. Specifically, Title III of the ADA applies to private institutions like Augustana College. Title III covers businesses that provide goods or services to the public, such as stores, restaurants, bars, theaters, hotels, private schools, and doctors and dentists offices. The ADA also has requirements for making the physical environment more accessible so that architectural barriers that limit access by individuals with disabilities are minimized or removed.

For purposes of classroom accommodation, however, both the ADA and Section 504 require that institutions provide reasonable accommodations so as to enable a student with a disability to fully participate in our education programs and activities–including events, internships, clinicals, study abroad, and student worker positions.

See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic.

College is Different than K-12 for Students with Disabilities

K-12 students are protected under Section 504 and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). In K-12, students are given accommodations or alternate classes because the school identified that support was needed and determined that the student qualified for the support. Often K-12 services and supports are driven by parents, teachers, and support personnel. Students might not fully understand their needs, their rights, or how to advocate for their needs. In college, students must initiate the process to receive accommodations by contacting Disability & Access Resources.

While Section 504 applies in the K-12 context, a key difference in the postsecondary level is that students generally have the responsibility to identify their disability, provide documentation, and request accommodation. Due to gaps in the transition between K-12 and College, students may not be aware that they need to initiate the accommodation process or may not be aware that they can get support at the collegiate level. It is important to be aware of this transition gap, as it can often create confusion for students and can delay a student’s request for accommodations due to a misunderstanding of how the process to obtain an accommodation is initiated. Instructors should be mindful of this when requests feel “last minute.”

See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic.

Confidentiality

Disability information—including accommodations, disclosure, and medical documentation—is covered under FERPA, and is held on a strict need-to-know basis. DARS only shares information about a student’s disability with instructors if it is crucial to the determination or delivery of an accommodation. Instructors cannot ask for specific information about a student’s diagnosis or disability beyond what the student or DARS volunteers. If understanding the diagnosis feels critical in determining an accommodation, instructors are encouraged to discuss this with DARS.

Disability information may never be shared with other students, other instructors, or parents unless the student has given explicit consent in writing to the person who will be sharing the information. Conversely, conversations with an instructor about a student’s accommodations may need to be shared with the student if there are any issues or discussions regarding their accommodations that may affect their performance. If you have any questions about what is confidential, please do not hesitate to ask Disability & Access Resources.

Academic Integrity vs Access

Under ADA and Section 504 law, the College is required to provide accommodations to qualified students as long as the accommodations are reasonable and do not fundamentally alter academic requirements that are essential to the program or class outcomes. This means that we must reasonably modify policies, practices, and procedures to ensure not only access, but inclusion and non-discrimination for students with disabilities. In other words, as long as the request is reasonable and the student is qualified, accommodations must be implemented even if they require modification of policies and/or procedures.

Students with disabilities must be qualified for their program or class, meaning that they must meet all the academic and technical standards for admission or participation (34 CFR § 104.3) with or without reasonable accommodation. They must be able to maintain good standing and meet all the program requirements, even if they have to use reasonable accommodations to do so.

What constitutes a reasonable accommodation varies case-by-case and depends on the class and the student’s disability. To be reasonable, an accommodation must not create an undue financial burden or administrative hardship for the institution. It is important to note, however, that the standard for what constitutes an undue burden or hardship is very high; inconveniences and even very tight budgetary pressures are generally not considered undue burdens. Accommodations must also not pose a direct threat to the student or others. An accommodation must uphold all academic standards without changing core objectives, while providing the student with necessary flexibility to reduce the barriers presented by their disability.

Who Qualifies for Accommodations?

Any student who has a diagnosed disability–either long-term or short-term–may qualify for accommodations. The ADA defines a person with a disability as a person who has a “physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities; a person with a record of such impairment; or a person who is regarded as having an impairment” (ADA § 12102). The ADA also contains a non-inclusive list of major life activities, in which things like learning, reading, thinking, and concentrating, which are central to being a college student, are included.

Some disabilities or circumstances that may qualify include:

- ADHD

- Anxiety

- Autism

- Blind/Low Vision

- Cancer

- Chronic Health Conditions

- Chronic Migraines

- Chronic Pain

- Concussion recovery

- Deaf/Hard of Hearing

- Depression

- Diabetes

- Migraines

- Physical Disability or mobility challenges

- Surgery recovery

The Accommodation Process

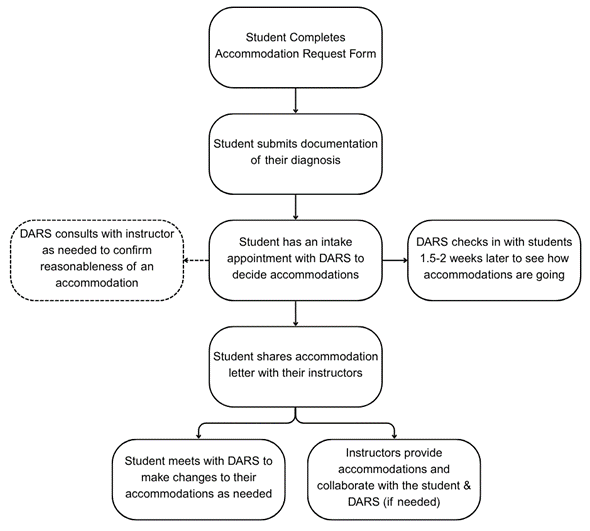

The accommodation process starts with disclosure, which can happen in a variety of ways. Disclosure is not a guarantee of accommodation, but it initiates the process of determining whether and what accommodations are needed and reasonable. Disclosure can be a student submitting the online intake form on the DARS website, sending an email to DARS, or mentioning their disability or struggles to an instructor or staff member who then refers the student to DARS.

Regardless of how the student finds their way to DARS, they can expect to go through the same process. This process can start at any point in the semester, and DARS can approve adjustments to accommodations at any point if changes are warranted—there is no deadline for when a student must request accommodations, as we are always obligated to respond to a student’s request for accommodations, regardless of when that occurs. Accommodations are, however, prospective only and are not offered retroactively.

Regardless of the type of disability, all students complete the same process:

- Student completes the Accommodation Request form

- This gives DARS information about the student, their diagnosis, and their past use of accommodations. Students may upload documentation when completing this form.

- Student submits documentation of their diagnosis

- Documentation takes many forms, but it is usually either Educational (from K-12 or a previous institution) or Medical (from the team overseeing the student’s disability, including psychologists).

- Student has an appointment with DARS

- In this appointment, we review the submitted documentation related to the student’s disability and discuss how their disability impacts their classes and other aspects of college life. We ask a variety of questions to get a full understanding of the impact through the student’s self-report and our own professional judgement.

- We discuss the courses the student is enrolled in and how their disability may impact their learning with the student, to decide the best accommodations to minimize or remove any anticipated disability-related barriers. This conversation is interactive and can also require the input of the instructor(s) to help determine which accommodations will reduce barriers for the student without altering the learning objectives of the class. After this meeting, DARS generates the student’s accommodation letter describing approved accommodations, and the letter is emailed to the student. In the case of short-term accommodations, a flag is raised in Starfish, which triggers an automated accommodation letter to be emailed to each of the student’s instructors.

- Student shares the accommodation letter with their instructors

- Students are encouraged to email their accommodation letter to their instructors as soon as possible so they can start receiving their accommodations. DARS encourages students to have a conversation with their instructors about what the accommodations will look like in each class. Instructors are required to provide approved accommodations. Students should not be forced to negotiate their approved accommodations with their instructors. If there are any questions or concerns with the approved accommodations, instructors should reach out to DARS as soon as possible.

- Check-ins

- DARS always follows up with students 1.5-2 weeks after their accommodation appointment to see how their accommodations are working. If the student hasn’t yet shared their letter with instructors, DARS will encourage them to do so.

- If the student or instructor has questions at any point, DARS is always available to clarify, collaborate, or identify alternatives for accommodations that create challenges in particular courses. Finding appropriate accommodations can require an on-going interactive process.

Part of the accommodations process is determining whether a student is qualified and if the accommodations they need are reasonable. The student knows their disability best, but DARS and instructors know Augustana best. The goal is to implement the most effective accommodations. while the effective accommodation may not be the student’s first choice or otherwise preferred accommodation, it may still achieve the goal of accessibility while meeting class outcomes or college needs.

Questions or concerns regarding a student’s qualification to be in a course, with or without an accommodation, should be directed to DARS. DARS will help facilitate conversations with the student, the instructor, and College leadership and legal counsel as appropriate in these situations. All students have the right to appeal accommodation decisions to the Director of Civil Rights at the College who serves as the College’s Section 504 Appeal Officer.

Student, Instructor, and DARS Responsibilities

The student, instructor, and DARS all play an important role in the interactive process to identify and implement reasonable accommodations.

Student Responsibilities

- Initiate the accommodations process by disclosing their disability and providing documentation to DARS.

- Meet with DARS to discuss the impact of their disability on coursework and possible accommodations.

- Know their approved accommodations

- Email their instructor(s) a copy of their Accommodation Letter and initiate a discussion about how their accommodations will be used in each of their courses.

- Understand that an instructor does not have to provide an accommodation until the student provides an Accommodation Letter, even if they have disclosed to the instructor that they need assistance due to a disability.

- If they are utilizing testing accommodations, communicate with their instructor at least 5 business/school days before the test.

- Contact DARS if accommodation modifications are necessary or if accommodations are not being provided appropriately.

- Communicate with their instructor(s) as needed to use their accommodations and confirm they are on track for success.

Instructor Responsibilities

- Provide accommodations after receiving the student’s Accommodation Letter or Starfish flag.

- Work with the student to discuss a plan for their accommodations in their classroom.

- If the student is using testing accommodations, submit the testing accommodation form at least 5 business/school days before the test.

- Contact DARS as soon as possible with any concerns or questions about implementing the student’s accommodations.

- Instructors are not required to provide accommodations without receiving from the student an Accommodation Letter issued by DARS or receiving an accommodations-related communication from Starfish.

- Avoid asking the student information about their diagnosis or disability.

Accessibility Provider Responsibilities

- Determine the accommodations that are reasonable and needed based on documentation, discussion with the student, and the classes being taken.

- Schedule student exams, after receiving the testing request from the instructor.

- Confer with instructors as needed to determine reasonableness of accommodations.

- Write the Accommodation Letter and email it to the student or raise a Starfish flag.

- Dialog with instructors regarding any accommodation concerns or challenges for their class.

- Work with the student to ensure accommodations are being provided and are successful.

- Enforce any issues with accommodations not being provided appropriately.

- Provide support or coaching to students.

- Collaborate on bias or discrimination issues.

- Provide professional development to instructors and staff related to accessibility.

Appeal Process

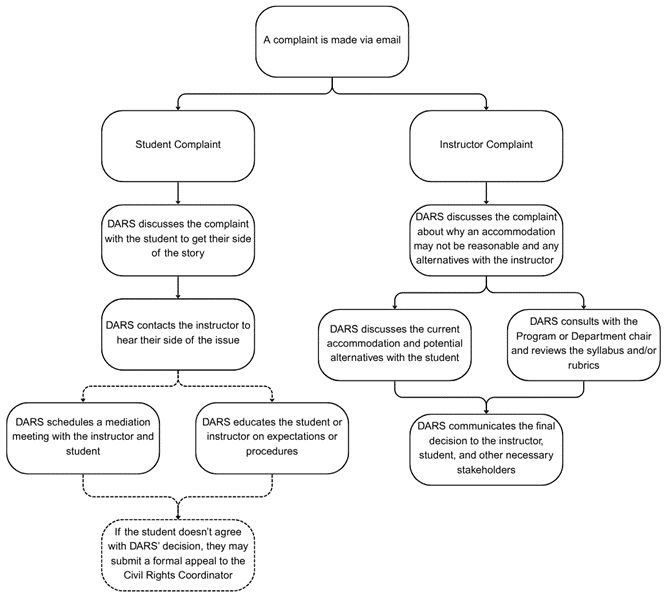

If students feel their accommodations have not been provided appropriately, they have been unfairly denied accommodations, or have been discriminated against for their disability, they have the right to appeal. Similarly, instructors who believe an accommodation is not reasonable or who otherwise witness discrimination should contact DARS. The goal of DARS is to listen to and collaborate with all stakeholders as much as possible. We are mediators, but we must also meet the requirements of the law and accommodate students in ways that enable their success as outlined in the law.

Student Appeals Process

While a student may skip this step, it is preferred that a student share concerns about accommodations with DARS prior to filing a formal appeal. This provides DARS with the opportunity discusses the complaint with the student and identify possible solutions. If the complaint involves an instructor, DARS will generally contact the instructor to understand their perspective of the situation before addressing the concern. The next steps depend on the situation, but can include mediation or education of the student or instructor. When the complaint involves an accommodation decision made by DARS that cannot be resolved by discussion, students can then submit an Accommodations Appeal form to work with the Civil Rights and Title IX Coordinator. If students feel they have been discriminated against because of their disability, they can submit a Bias Incident Report.

Instructor Options

If an instructor feels an accommodation is not reasonable for a class or is a fundamental modification of the learning outcomes, instructors should email DARS (disabilityservices@augustana.edu). We will have a discussion about why the accommodation may not be reasonable and any possible modifications or alternatives to the accommodation. DARS may request access to the syllabus or grading rubric to review the learning objectives and/or consult with your Department Chair or Divisional Dean in order to better understand what is a reasonable accommodation. As part of the process, we will consult with the student to talk about the accommodation and possible alternatives.

If you witness discrimination against a student or another staff member because of their disability, you submit a report to the Civil Rights and Title IX Coordinator.

Common Accommodations

Provided below are brief descriptions of common accommodations. This is not a comprehensive list. Please remember that the way some accommodations are provided depends on the student and the class. DARS knows some situations are complex and might require collaboration. If you’re not sure how an accommodation works or how to put it in place, feel free to ask DARS.

Adaptive Furniture in Classroom – The student may need a classroom modification such as a different desk and/or chair. If the equipment is not already available within the classroom, DARS will work with Facilities to make sure it is available.

Allow Audio Recording of Class – The student may audio record lectures. The student is responsible for providing their own recording device (e.g., SmartPen, tablet, phone, notetaking software). Any electronic text, notes, or recordings made from any recording, as well as any other materials provided for accommodation purposes are for personal use ONLY and cannot be shared or posted. The student and the instructor will sign an agreement confirming this policy.

Allow Short Breaks During Class or Exams – The student may require a short break during class or exams. How the break is used and what it will look like will depend on the student's needs. The student may not leave a proctored area unless arranged with the instructor. Breaks during class and exams are separate accommodations and will be listed as such on the accommodation letter.

Alternatives for In-class Presentations – The student should be provided alternative assignments to making in-class presentations unless presentations in front of a group are part of the goals or learning outcomes for the class. Alternative presentations could include, but are not limited to: a one-on-one presentation with the instructor, presenting to a smaller group, or recording a video presentation. Variations should be decided by the instructor in collaboration with the student, and DARS if needed.

Alternative Format Textbooks or Materials – Students may need a textbook in a different format such as a Braille, audio, or e-text. They may also need materials to have large font size (16pt+) or be provided in an electronic format that can be enlarged and read aloud. DARS is available to consult regarding this accommodation if alternatives are not immediately available.

Break Down Large or Complex Assignments – Students might benefit from large assignments or readings being broken down into more manageable chunks. This can be accomplished in many different ways, including breaking a 10-page paper into two 5-page papers, splitting long or complicated questions into multiple questions, or splitting a 50-page reading into five 10-page readings. This can be done on the same deadline or assigned over a couple of days. The instructor should determine an appropriate way to break down the assignment.

Captions – Videos and audio material should have captions turned on. PowerPoint and Google Slides also have options for live captions during lecture. Caption options are typically found in the settings at the bottom of the presentation view or video. If you record your own videos, you can upload to Youtube for auto-generated captions, or import it to a video editing software. You can use auto-generated captions or upload a transcript.

Class Notes – Class Notes accommodation ensures students with qualifying disabilities have notes similar to what they would take if their disability did not interfere with note-taking. This accommodation does not replace attendance.

Notes can be provided in several ways and the method is decided by DARS and the student, depending on how the disability impacts note-taking. Students can use LiveScribe Smart Pen, a smart pen that audio records and computerizes handwritten notes; Instructor-provided or classmate-provided notes; or notetaking software, such as Glenio or OtterAi (paired with a recording accommodation).

When a student has accommodations for classmate-provided notes, instructors should make a general announcement to the class asking for volunteer note takers. The notes can be provided in a variety of ways, but the notetaker cannot know who is receiving them. Directions for providing notes to the student anonymously will be in the student's Accommodations Letter.

Deadline Modification - Occasionally, a student may need flexibility for a specific assignment. The student is expected to adhere to all deadlines as per the syllabus unless discussed with the instructor at least 24 hours before the original deadline. The length of the extension depends on the student’s accommodations and any contextual situations surrounding the assignment.

Deaf and Hard of Hearing Accommodations – Accommodations for Deaf/Hard of Hearing students may include preferential seating, ASL interpreters, captioned videos, transcriptions of audio materials, CART real-time class captioning, and Assistive Listening Devices. Contact DARS for specific information about these accommodations in your classroom.

Grammar and Spelling – If the student has a language-based disability and correct grammar and spelling are not an important goal for the course, points should not be taken off for incorrect grammar or spelling.

Memory Aid – A memory aid is a tool used to help students trigger recall for information they studied but may have a hard time processing or remembering. The memory aid does not list all the facts or concepts, but helps the student remember. The information on the aid must be approved by the instructor. A memory aid can include a formula sheet on an exam not testing memory of the formulas, drawn notes, an outline, songs, acronyms, etc.

Modification of Attendance Policy (MAP) – Students are usually expected to follow classroom attendance policies, however, some disabilities may cause the student to miss class occasionally. MAP provides additional flexibility to the college attendance policy; however, instructors are not required to change any important parts of the class. The student remains responsible for completing and submitting any work that was due the day of the absence, however, the student will be granted a minimum of 24 hours to complete assignments/reschedule exams after an absence due to health conditions, as long as the logistics of the activity allow, i.e., make up of in-person science labs with complex set-up may not be feasible. The actual rescheduled due date depends on the number of consecutive days missed. For example, if three days in a row were missed, 24 hours would not allow enough time to make up the work.

MAP holds students responsible for any consequences of their absences, but changes the number of absences before those consequences result in penalties (i.e., regular attendance allows 3 absences without penalty, 2 additional absences with penalty, and recommended withdrawal or failure at 5 absences. 20% MAP allows 6 absences without penalty, 2 additional absences with penalty, and withdrawal or failure at 8 absences.)

Speech-to-Text Software – Text-to-Speech software (e.g., Read&Write, JAWS, Dragon Speaking Naturally, Dictation) allows students to speak aloud and the software will transcribe their words to text. Students may need to utilize this accommodation during an exam, for essays, or in-class activities. The software will be provided by DARS or the student.

Testing Accommodations – Students may be approved for extended time for tests and quizzes. Students who use extended test time should take their test in the Testing Center. Students may also need to take tests in the reduced-distraction environment of the testing center or take the exam at a different time of day. They may need to have their test read to them or have someone write their tests for them while the student says the answer out loud. The student will inform their instructor that they want to use their testing accommodation at least 5 days ahead of the exam, and the instructor will fill out the Testing Accommodation Form to notify the testing center so the test can be scheduled.

Text-to-Speech Software – Text-to-Speech software (e.g., Read&Write, JAWS, Narrator, VoiceOver) allows digital materials to be read aloud to students. Students may need to use this during an exam or in-class activities, along with headphones to hear the speech privately. The software will be provided by DARS or the student.

Paper Materials Instead of Digital – Students may need PowerPoints, readings, or other materials provided on paper, as available. This can also include submitting handwritten assignments instead of typed assignments. This is typically to help with visual strain or light from a computer screen. The instructor is responsible for providing paper materials.

Preferential Seating – Students may need an assigned seat in the classroom. Where the seat is located is dependent on the student’s needs. Student needs may change throughout the semester.

Priority Registration – The student will be the first in their class cohort to be able to register for classes. For example, if the student is a sophomore, they will have first choice among sophomores. This accommodation is coordinated between DARS and the Registrar’s Office.

Quantitative Reasoning Substitution – Substitutes courses that will fulfill the Quantitative Reasoning degree requirement (Q suffix). Consideration is given to the student’s major or intended major before DARS grants this accommodation. Students are provided a list of approved alternative classes that will fulfill the Q suffix for them. Students share this list and their accommodation letter with their advisor and work with their advisor to select the course they will use to fulfill the Q suffix. Once the student selects the course they will use to fulfill their Q suffix requirement, they must notify DARS and the Registrar’s Office of their selection to ensure the course is coded correctly to fulfill this graduation requirement in their “My progress” degree audit in Arches.

Second Language Substitution – Substitutes foreign culture courses for second language courses to fulfill the Second Language degree requirement. Students are provided a list of approved alternative classes that will fulfill the second language requirement. Once the student selects the courses they will use to fulfill their Second Language requirement, they must notify DARS and the Registrar’s Office of their selection to ensure the courses are coded correctly to fulfill this graduation requirement in their “My progress” degree audit in Arches.

Use of a Computer – Students may need to use a computer in the classroom for reasons such as: typing instead of handwriting, using a screen-reader program, using a voice-to-text program, or using a screen magnifier. The student is responsible for providing their own computer, with the exception of when they are taking exams or quizzes. Students and instructors can request to use a College-owned computer, as long as required assistive software is available on the device.

Creating a Disability-Inclusive Campus: Disability Identity and Cultural Context

History and cultural elements affect how students with disabilities experience the world and our campus. Similar to other minority groups, disabled people have been historically oppressed and segregated from the rest of society (Baynton, 2001). However, disability culture and history are seldom discussed or celebrated the way other marginalized communities are. These topics can have a significant influence on how, when, to whom, and IF students disclose their disability. Awareness of disability culture, identity, and historical context is important as we work toward developing a disability-inclusive campus culture that celebrates disability as another form of diversity.

Ableism is the concept of oppression or bias through assigning value to people’s bodies and minds based on societal constructs of normalcy, productivity, desirability, intelligence, and fitness. Ableism has deep roots in eugenics and colonialism (Dolmage, 2011) and is still present in modern society in quiet ways that creep into our words and perspectives.

“While we may acknowledge we are racist, we barely know we are ableist.”

Disabled people commonly internalize ableism and believe their disability makes them less capable or worthy (Charlton, 1998). The passage of Section 504, the Disability Rights movement, and the ADA had pivotal roles in establishing the rights and societal integration that people with disabilities have today, but the work on social perceptions of disability is still ongoing.

In the field of disability, there are two primary models of conceptualizing disability: the medical model and the social model. The medical model is the oldest and subscribes to the idea that disability is created because of an individual’s physical or psychological impairment. In this model, disability is something that needs to be cured to return the person back to “normal” (Shakespeare, 2010). This model shares its roots with the eugenics movement of the 1800s and remains prevalent in today’s industrialized society—especially in medical, professional, and policy-driven spheres. By framing disability as a deficit within the individual, the medical model implies that something is inherently wrong or undesirable about the person and can perpetuate disability stigma.

The social model states that disability is created by environmental or prejudicial barriers, rather than from a flaw or deficit in the person with the physical or psychological condition (Shakespeare, 2010). For example, the problem is not that a person uses a wheelchair, the problem is a building that lacks a functioning elevator. The Disability Pride movement flourishes under this model and is preferred by disability advocates because it emphasizes inclusion and acceptance of identities. The social model most closely aligns with Augustana's mission, values, and strategic plan.

Not every person with a condition that meets the legal definition of disability identifies as disabled. Some people strive to gain some sense of societal “normalcy” and prefer not to acknowledge their disability. Others have embraced the idea of disability pride and work to dismantle disabling environments. It is also common for disabled people to feel as if they fit in the gray spaces between these perspectives—feeling pride in who they are, but practicing discernment with whom they share that identity, or sometimes not feeling “disabled enough” to claim the identity.

Disability identity is further complicated by other cultural, racial, ethnic, or religious values. Augustana is proud of our diverse student body, which is a mixture of many cultures, religions, and racial/ethnic backgrounds. Along with this cultural diversity comes variable perspectives of disability. Many students’ families or cultures have shunned disabilities as taboo flaws to be kept secret. Students are told they just need to work harder or “deal with it” rather than get help. These cultural norms affect the willingness of our students to disclose their disability so that they can get the accommodations they need. Many of these students either never seek accommodations or only do so when they are failing.

See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic.

Inclusive Language

Language is power. The way we use language can have an impact on students with disabilities due to unconscious bias ingrained in commonplace words. A small difference in one word can make people feel accepted, or it can be dehumanizing. People with disabilities typically fall into two categories for preferred language: person-first and identity-first. Neither is wrong, but to be inclusive, ask the disabled person’s preference and respect their choice—just as you would a preferred name. In group settings, interchange both language models or ask the group to come to a consensus. Disabled people can change their preferences at any time and in different contexts.

Person-first Language

Person-first language was created in the 1970s as a way to reclaim status of being a human first and disabled second (Carter, 2023). Person-first language sounds like “I have a disability” or “person with a disability”. This language style has been adopted as the universal professional standard as a way to create equality and separate the person from the stigma of their disability. It is often the preferred language for those with intellectual disabilities, who find themselves continually needing to remind people of their humanity. However, many disability advocates have renounced this language style and say that person-first language buys into the exact negative stigma it was meant to avoid by labeling the word ‘disabled’ as bad.

Identity-first Language

Identity-first language started reappearing in the 1990s and subscribes to the idea that being disabled is not shameful, it is a part of life, and celebrates acceptance of differences. Identity-first language sounds like “I am disabled” or “disabled person”. Many disability advocates prefer this language style because they feel their disability is inseparable from who they are (Ladau, 2015). Identity-first language is popular with the younger generations who are actively choosing to be more open and renounce stigma. There are also some communities, mainly the Deaf and Autistic communities, that use this language exclusively.

Common Words/Phrases to Avoid

Regardless of which preferred language you use, there are common phrases you should seek to avoid.

| Avoid | Use |

|---|---|

| Handicapped, Special Needs, Differently-abled, Impaired, Crippled/Crip (unless initiated by the disabled person) | Disability, Disabled, Person with a Disability |

| Psycho/Crazy/Insane | Wild, confusing, impulsive, reckless, etc. |

| Dumb/Stupid/Retarded | Ignorant, impulsive, reckless, uninformed |

| Visually impaired | Blind or Low-Vision |

| Deaf mute/Deaf and Dumb/hearing impaired | Deaf or Hard of Hearing |

| Wheelchair-bound | Wheelchair-user |

| Midget | Dwarf, Little person, has dwarfism |

| Low-functioning/High-Functioning (Autism) | Autism, Low support needs/High support needs Autism |

| Deformed/Disfigured | Describe the condition or appearance |

| “Are you deaf/blind?” | “I can’t believe you missed that!” |

| “Can’t you see/hear?” | “I can’t believe you missed that!”, “Is this something you can do?” |

| “What’s wrong with you?” | Avoid asking this, questions about if they have a disability or how it happened |

| Suffers from/Victim of/Stricken with | Has a disability, Has ….. |

| Calling someone brave or an inspiration (because they have a disability or did something normal) | Acknowledge an accomplishment the same as you would for someone who is non-disabled |

| Regular/Normal/Healthy/able-bodied (when talking about people without disabilities) | Non-disabled |

| “You don’t look disabled”, “you’re too young to have/be…”, or “you look fine to me” | Avoid making these statements. They minimize their experiences and challenges |

If something feels wrong or you’re not sure if it’s appropriate, consider rephrasing. AutisticHoya has a great list of terms to avoid and alternatives.

Disability Etiquette

When interacting with people with disabilities, it is important to treat them with respect, but each person and disability type will have different needs from you during an interaction. The disability etiquette tips below can help you navigate these interactions.

General Tips

- Disabled people deserve autonomy and dignity

- Don’t assume capability or incapability.

- Always ask if someone would like help before swooping in to do something.

- Use inclusive language.

- Ask about their preferences. They know their disability, wants, and needs best.

For Physical and Mobility Disabilities

- Do not touch mobility equipment – even if it is not in use. If something seems like it is in the way, ask if it can be moved. There may be a specific reason it is placed where it is.

- Be aware of conversational distance, especially when talking with someone who is seated while you are standing. Neck strain in mixed-height conversations can be painful. Standing a little bit further back can ease this.

- If you see someone struggling who looks like they may need help, offer help first instead of automatically doing it, and respect their response. If they decline, respect their response. If they say yes, ask how you can help and follow their direction.

- Recognize that physical disabilities can vary, and the mobility tools used may vary as well.

For Blind/Low-Vision

- Identify yourself when entering a conversation and when leaving.

- Offer your shoulder or arm as a guide rather than grabbing or pushing the person.

- When guiding someone, describe visual information, locations of items, obstacles, or environments.

- Do not pet or talk to a guide dog.

- Do not assume ability to see objects or writing clearly, conversely, do not assume they can’t see. Vision is a spectrum.

- Recognize that lighting conditions change visual ability.

For Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing

- Get their attention before starting a conversation.

- Look at and speak directly to the person, even if they use an interpreter.

- Face the person and speak in a normal tone and volume without exaggerated facial expressions.

- Be willing to write things down or use speech-to-text apps.

- If they miss something in the conversation and ask you to repeat yourself or explain, don’t say you’ll tell them later.

- If asked to repeat yourself, rephrase what you said and repeat it differently. Sometimes specific words or tones can be harder to hear than others.

- Don’t assume their level of hearing or that they can’t speak just because they are Deaf/Hard of Hearing.

- Recognize that group settings and settings with lots of background noise are more difficult to navigate.

For Speech Disabilities

- Do not speak for them or try to finish their sentences.

- Be patient. Give time for them to formulate and speak their answer, even if it means waiting a while or having a delay in the conversation.

- If you do not understand what they are saying, ask them to repeat and repeat back what you understood.

- Ask them to write their message or use a text-to-speech app.

- Don’t dismiss their thoughts or opinions or assume they don’t have any just because it is difficult for them to communicate them.

- Recognize that speaking in group settings, such as class, can be stressful or challenging. It’s not always from a lack of engagement and participation.

For Neurodivergent/Learning Disabilities

- Be patient.

- Provide clear, explicit instructions in written and verbal formats.

- Provide concrete examples with visual examples when explaining, and explain multiple different ways.

- Ask for clarification of intent or meaning if you feel a comment was hurtful or inappropriate. Sometimes this is just a miscommunication.

- Don’t assume a lack of intelligence just because they take longer or learn differently.

- Recognize that neurodivergent disabilities are multi-systematic and affect more than what is commonly portrayed in media, and can present in multiple different ways.

For Invisible Disabilities

- Recognize that disclosing their disability comes with risk. Believe them when they disclose to you, and honor their privacy by not sharing their disability with others.

- Ask about their support and accessibility needs; don’t assume.

- Try to understand their lived experience through conversations without being invasive.

- Don’t assume their disability is minor or not impactful just because they “look fine” or you can’t see it.

See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic.

Universal Design for Learning Principles

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a concept, based on the principles of Universal Design in architecture, that ensures accessibility for disabilities is built-in to the learning environment to lessen or eliminate the need for accommodations. This framework is meant to provide flexibility for all students, not only those with disabilities, in a way to reduce barriers and accommodate differences in learning without compromising expectations. The idea of a full curriculum overhaul is daunting, but you can start small and build out, semester by semester.

UDL does not replace the need for accommodations, but it may reduce students’ reliance on them. The more flexibility you build into your classroom, the less students need to be singled out to be successful. Because of this, UDL creates more successful outcomes for students academically and professionally. Students who feel supported and heard are retained students.

The Basic Principles

- Multiple means of representation

- Provide different ways to learn the same materials (e.g., videos, articles, modules, hands-on activities, textbook readings, use models)

- Use captions

- Use accessible digital materials

- Post your lecture PowerPoints or notes before class

- Encourage students to exchange class notes

- Link to additional resources

- Connect to prior knowledge

- Multiple means of expression

- Offer different options for assessment

- Eg, exams with multiple types of questions or graphics, essays, presentations, videos, models, creative projects, debate

- Allow for flexible deadlines or grading

- Consider allowing corrections to show improved performance

- Cumulative assignments with feedback checkpoints

- Offer different options for assessment

- Multiple means of engagement

- Provide prompt feedback

- Consider allowing corrections – students learn from mistakes

- Use rough drafts for assignments

- Give students choices and options to enhance engagement

There are a variety of wonderful resources that you can implement UDL in your classroom. See the Additional Readings and Resources section for more information on this topic. You can also check out the Augustana CELTS Moodle page for more resources.

Creating an Accessible Classroom

In order for students to be successful, they need to be able to physically and cognitively access class lectures and learning materials. This means we must consider accessibility needs related to physical space, accommodations listed in students’ accommodation letters, and the delivery and ethos of the class itself. Below are some considerations that help make your courses more accessible for everyone:

Alt Text on Images – On digital materials with graphics, ensure that the images have alt text or captions that make sense for the image. Alt text is a hidden caption that allows blind/low vision people or others using screen readers to access the image. In Microsoft products, right-click on the image. In Google products, right-click on the image or go to image options.

Background Choice – When choosing your background designs for PowerPoints, choose a background that is simple with high contrast and limited variation. If you’re not sure if something has enough contrast, you can check the colors online through a color checker. It may seem more interesting to look at curated designs, but this can make it hard for some students to follow along. Simple backgrounds are less distracting and easier on the eyes. White or light backgrounds with black text is a good default. Alternatively, deep, dark backgrounds with white text. Augie blue and gold is considered high contrast, but use caution as overuse of the bright yellow can cause eye strain for some students.

Captions – When showing a video, be sure the captions are turned on. Regardless of whether you have a student with an approved accommodation, captions can be beneficial for all students. Captions are especially helpful when the audio is poor quality, the sound doesn’t reach the back corner, or for non-native speakers of the language spoken in the video. You can also include live captions of your lectures with PowerPoint or Google Slides. The option to turn on captions is typically in the bottom corner when in presentation mode.

Color Choice – Use high contrast colors. Try to avoid choosing colors that are close in tone in tone or saturation—especially for background and text. Microsoft has a checkable option under the text color to only use high contrast colors. Try to also avoid using color as the sole way to distinguish information, as this can make the content inaccessible to those who are color-blind. Instead of or in addition to color, draw attention to information through different line or arrow types or text types such as bold, italics, or underline.

Hyperlinks – When directing students to a link, avoid pasting the whole URL for them to click. This is inaccessible to students using screen readers and distracting for others. Use hyperlinks over descriptive text. Avoid using ‘click here’ in your text, instead try “visit Disability & Access Resources’ Accommodation Request form”. If a hyperlink is not possible, use a short URL (i.e. augustana.edu/disability). In Microsoft products, hyperlink by highlighting the text and right clicking. In Google products, highlight the text and right click or look for the chain-link in the text menu along the top.

Desk Spacing – Whenever possible, try to leave plenty of room to navigate the aisles between rows of desks and between the rows themselves. Break up long rows with aisles or group desks into pods. Students with mobility disabilities may need extra room to navigate or may need to use some aisle space for their mobility equipment. It can also be challenging to move between long rows of desks and chairs.

Headings and Lists on Documents – On digital materials, use the text styles to create headings rather than just increasing the size manually. Although it may look the same visually, screen readers don’t recognize increased text size as a heading and aren’t able to indicate the start of a new section. Using the text style means that the screen reader can recognize a new section is starting. Similarly, use the bullets and numbering function to write out lists instead of just starting a new line. Screen readers can’t tell you’ve created a list unless you use one of these functions.

Plain Language – Use plain language as much as possible in directions. This means using simple words and sentence structures with short paragraphs so that it is easier to read and comprehend. Be direct and explicit in your directions. Leave nothing to assumption.

Scanned Materials – Try to avoid using scanned materials or articles. When documents are scanned, the scanner creates an image of the page, but doesn’t usually read the individual letters to make text. This means that students who use text to speech or screen readers cannot access the material. Use webpages, e-text books, or digital articles instead. If you must scan a material, use an OCR (optical character recognition) program after scanning it to extract the text. There are many free OCR programs online, and we have access to limited licenses for paid programs on campus. If you need help converting a scanned document, please contact DARS.

Using AI for Accessibility

AI can be a helpful tool for accessibility. It can streamline processes and give suggestions for accessible verbiage or classroom activities. There are ways that it can be used responsibly, without compromising academic integrity.

Instructional Use

AI can help with a variety of tasks that can help you simplify and maximize accessibility in your classroom.

- Ask ChatGPT or another AI to convert a high-register, academic text into plain language or have it check to see if your own words are clear and concise.

- Some AIs, such as onlineOCR.net (free), PDF24 (free), Adobe Acrobat Pro, OpenBook, and others, can convert inaccessible scanned documents into accessible documents through OCR conversion.

- You can ask AI to suggest UDL-based classroom activities based on a topic or lecture notes.

- Use AI, such as JamWorks, Glenio, or OtterAI (offers basic free plan), to record and transcribe your lecture, then pull out the most important points in the form of lecture notes.

- Analyze data more quickly.

Possible Student Use

This is intended to give you ideas for how you might allow students to use AI for accessibility.

- Ask ChatCPT, Goblin.tools, or another AI to rephrase directions or break-down and re-explain concepts.

- Use Lex.ai or Grammarly to do a spelling and grammar check.

- Ask AI to create to-do lists from a big assignment prompt or a list of homework and due dates.

- Brainstorm paper topics, interview questions, or sources for an assignment.

- Upload notes or a lecture recording to create study quizzes.

- Ask AI to summarize articles to determine if they would be helpful for a paper or to check for reading comprehension.

- Transcribe lecture recordings into a readable document.

Limitations and Cautions

Like all tools, AI has its limitations and perils of use. Firstly, AI does not replace accommodations. It can help aid in the implementation of accommodations or in making the classroom environment more accessible, but accommodations need human input to be successful. Secondly, while AI is constantly changing and improving, it can still get things wrong and produce incorrect information or odd verbiage that doesn’t quite fit. Your expertise, knowledge, and professional judgement as the instructor of the course is the most helpful in providing student accommodations.

When considering student use, it is important for students to talk with instructors or for instructors to set clear guidelines about AI use and what is acceptable before using it in courses. Just as students deserve to have instructors who are engaged in teaching and the classroom, instructors deserve to have engaged learners using their own thoughts and ideas.

Recommended Syllabus Language

At Augustana it is not required to have a section about obtaining accommodations in the syllabus. However, this guidance is highly recommended and can make a big difference for students. Having a syllabus section can make students feel supported and help them realize that there are resources available to them. Here is the suggested syllabus language. Please feel free to use it directly in your syllabus:

Augustana College is dedicated to fostering a learning environment that supports the diverse needs of all students. If you discover any barriers to your learning in this course, please feel free to discuss your concerns with me.

If you have a disability or believe you may have one, Disability & Access Resources (DARS) can help make sure you have the support you need. If you have any questions or concerns about getting support for your disability, you can email disabilityservices@augustana.edu.

If you have already been approved for accommodations at Augustana College through Disability & Access Resources, please share your Accommodation letter with me as soon as possible, and let’s discuss how I can help support your learning needs.

Additionally, if you do a pre-class survey at the beginning of the semester, consider adding a question that allows students to mark if they would like to talk about accommodations with you. This can be a low-stress, discreet way for students to disclose a disability to you. The question could look something like this:

Students with disabilities (learning, sensory, physical, mental health disabilities, etc.) are entitled to classroom accommodations. These are communicated to instructors via a letter from Disability & Access Resources (DARS). Please mark one of the options below.

- I have a letter and will get it to you soon (or have already given it to you)

- I’m in the process of getting a letter from DARS

- I’m not sure if I’d qualify for accommodations. Can we talk about it 1:1?

- I do not have or need a letter from DARS

Accommodations after College

Disabilities and accommodations do not disappear after students leave our campus for the final time. Although some accommodations may no longer be necessary, depending on their chosen career, disabled people can get accommodations from their employer through rights protected by Title I of the ADA, often through the HR department. The accommodations may look different, but they still exist. For some people, the workplace can be a more flexible and less demanding environment than college, which allows for more self-accommodations. Some career fields are also more flexible and attuned to accessibility needs. Our goal is to provide them the access they need at Augustana, so that they are successful in the next chapter of their lives. Regardless of the career or the disability, know that the support and advocacy skills we help students hone during their time at Augustana will continue with them into their next chapter.

Quick FAQs

Q: Why do I have to provide accommodations?

A: Accommodations mitigate barriers so students have equitable access to the learning environment. Students with disabilities—especially multiple disabilities—can experience very real barriers that inhibit their success.

Q: Do I have to provide all of the accommodations in the student’s letter?

A: Yes, you need to provide all of the accommodations if the student tells you they want to use all of their accommodations and if the accommodations are reasonable for your class. You do not need to provide the accommodation if the student tells you they don’t want to use it or if, after working with DARS, it is determined that the accommodation is not reasonable.

Q: Do students with testing accommodations need to use the DARS Testing Center?

A: It is highly preferred that students with accommodations use the Testing Center, as we can assure the student’s accommodations are met while maintaining test security.

Q: What can I do if an accommodation doesn’t feel appropriate for my class?

A: If an accommodation doesn’t seem appropriate, please reach out to DARS to talk about why this may not be appropriate and any alternatives. (See the Appeals Process section for more information.)

Q: We didn’t have this many students with accommodations in the past. What changed?

A: Accommodations in K-12 have increased the number of students with disabilities who graduate from high school. The number of people diagnosed with disabilities has also been increasing due to more accessible medical care and updated diagnostic criteria. This, combined with evolving assistive technology and reduced disability stigma, means that higher education is more accessible to more students with disabilities.

Q: What if the DARS Testing Center is not available when I want my student to take their test?

A: Unfortunately, the Testing Center has limited hours and seats, so we may not always be able to proctor an exam during the time or day you are administering the exam for the rest of the class. We ask that you provide at least 2 days for the student to take their exam, beginning no earlier than the normal exam date, in case your preferred date and time is not available.

Q: Who qualifies for accommodations?

A: Any student who has a diagnosed disability–that is either long-term or short-term–may qualify for accommodations. For a list of disability examples and the legal definition of disability, see the Who Qualifies for Accommodations section.

Q: Do accommodations “lower the bar” or compromise academic integrity?

A: Accommodations level the playing field to reduce the effect of added challenges brought on by a disability, but do not reduce standards. Disability & Access Resources (DARS) strives to balance disability needs and the right to accessible learning with academic integrity and instructors’ academic freedom. If an accommodation would compromise the learning outcomes of the class, it is not a reasonable accommodation and we do not provide it.

Q: If I have a student who doesn’t have accommodations, and I think they should, what do I do?

A: Until you receive an accommodation letter for the student, continue as normal. You may share a general reminder that DARS services are available, but you should avoid singling out student in particular.

Q: If I give Student X an accommodation, isn’t that unfair to the other students?

A: Accommodations don’t give disabled students an advantage; they give them a fair shot at success by removing disability-related barriers that non-disabled students don’t experience. Every student has different needs, and unless a course has been designed for UDL, that means providing different resources for success.

Q: Do I have to provide accommodations if the student hasn’t given me a letter?

A: If a student asks for accommodations, but does not provide you with a letter, you do not need to provide accommodations. If this happens, you should let them know that they need to meet with DARS. If they haven’t met with DARS yet, feel free to refer them.

Q: Why do I need to fill out the Testing Center form?

A: The testing form gives DARS all the information and instructions we need to administer the exam as securely and effectively as possible. It also gives us information about how to return the exam to you.

Q: If an accommodation goes against one of my class policies, which do I follow?

A: Accommodations are often variations to standard college policies and practices. They are not deemed “unreasonable” merely because they require a different approach or a modification of our standard policies or procedures. Unless you have worked with DARS and determined that the accommodation is not reasonable, follow the accommodation.

Q: The student didn’t give me the amount of notice listed on the accommodation letter. Do I still have to provide the accommodation?

A: Maybe. You should still make every effort to provide the accommodation if you can. If the shortened amount of time creates a significant logistical barrier to providing the accommodation, you do not need to provide the accommodation.

Q: How does the Modified Attendance Policy (MAP) accommodation affect the institutional attendance policy?

A: MAP adds additional time to the standard college attendance policy before grade consequences are felt (i.e., regular attendance allows 3 absences without penalty, 2 absences with penalty, and recommended withdrawal or failure at 5 absences. 20% MAP allows 6 absences without penalty, 2 absences with penalty, and withdrawal or failure at 8 absences).

Q: What do I do if I’m not sure how to provide an accommodation in my class?

A: If you’re not sure, just ask! DARS is happy to collaborate and discuss ways to implement accommodations. Sometimes, asking the student can also help because they know what works for them.

Q: I just received an accommodation letter for a student, and we only have two weeks left in the semester. Do I have to go back and change their grades or allow extensions for missing assignments?

A: No. Accommodations are not retroactive. They only apply to any class activities moving forward from the date the letter is received.

Additional Courses and Trainings

If you are interested in further professional development or online courses about how to build an accessible classroom, here are a few resources.

- AccessCollege: The Faculty Room. (n.d.). DO-IT. Retrieved April 25, 2025. Training Resources

- Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Online Resources for Academic Ableism. University of Michigan Press. Online Resource

- Teaching All Students, Reaching All Learners, including Students with Disabilities as Diverse Learners. (n.d.). Center on Disability Studies. Retrieved April 25, 2025, from Professional Development Course

Additional Readings and Resources

If you’d like to learn more about any of the topics addressed in this reference book, here are some additional readings for each topic. Topics are in order of appearance in the book.

Faculty Influence and Disability Pedagogy

- Baker, K. Q., Boland, K., & Nowik, C. M. (2012). A Campus Survey of Faculty and Student Perceptions of Persons with Disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 25(4), 309–329. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Becker, S., & Palladino, J. (2016). Assessing Faculty Perspectives About Teaching and Working with Students with Disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 29(1), 65–82.

- Cook, L., Rumrill, P. D., & Tankersley, M. (2009). Priorities and Understanding of Faculty Members Regarding College Students with Disabilities. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 21(1), 84–96. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Guest Pryal, K. R. (2023, July 3). Neurodivergent Students Need Flexibility, Not Our Frustration. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Article

- Houman, K. M., & Stapley, J. C. (2013). The College Experience for Students With Chronic Illness: Implications for Academic Advising. NACADA Journal, 33(1), 61–70. Peer-Reviewed Article

Pryal, K. R. G. (2022, October 6). When ‘Rigor’ Targets Disabled Students. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Article - Rehfuss, M. C., & Quillin, A. B. (2005). Connecting Students with Hidden Disabilities to Resources. NACADA Journal, 25(1), 47–50. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Sniatecki, J. L., Perry, H. B., & Snell, L. H. (2015). Faculty Attitudes and Knowledge Regarding College Students with Disabilities. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 28(3), 259–275. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Vogel, S. A., Holt, J. K., Sligar, S., & Leake, E. (2008). Assessment of Campus Climate to Enhance Student Success. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 21(1). Peer-Reviewed Article

Campus Climate and Student Support

- Garrison-Wade, D. F. (2012). Listening to Their Voices: Factors that Inhibit or Enhance Postsecondary Outcomes for Students’ with Disabilities. International Journal of Special Education, 27(2). Peer-Reviewed Article

- Herbert, J., Fleming, A., & Coduti, W. (2020). University Policies, Resources and Staff Practices: Impact on College Students with Disabilities. Journal of Rehabilitation, 86(4), 31–41. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Kauffman, J. M., Anastasiou, D., Felder, M., Lopes, J., Hallenbeck, B. A., Hornby, G., & Ahrbeck, B. (2023). Trends and Issues Involving Disabilities in Higher Education. Trends in Higher Education, 2(1), Article 1. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Kristi Wilson, Elizabeth Getzel, & Tracey Brown. (2000). Enhancing the post-secondary campus climate for students with disabilities. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 14(1), 37–50. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Leake, D. W., & Stodden, R. A. (n.d.). Higher Education and Disability: Past and Future of Underrepresented Populations. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 27(4), 399–408. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Marshak, L., Wieren, T. V., Ferrell, D. R., Swiss, L., & Dugan, C. (2010). Exploring Barriers to College Student Use of Disability Services and Accommodations. 22(3), 151–165. Peer-Reviewed Article

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2017). Characteristics and Outcomes of Undergraduates With Disabilities [Dataset]. Dataset Analysis

- Price, M. (2024). Crip Spacetime: Access, Failure, and Accountability in Academic Life. Duke University Press. Open-Access Book

- Trammell, J. (2009). Red-Shirting College Students with Disabilities. The Learning Assistance Review, 14(2), 21–31. Peer-Reviewed Article

Legal Context

- Auxiliary Aids and Services for Postsecondary Students with Disabilities. (1998, September). U.S. Department of Education. Federal Guidance

- Emens, E. (2012). Disabling Attitudes: U.S. Disability Law and the ADA Amendments Act. American Journal of Comparative Law, 60, 205–234. Article

- Grossman, P. (2001). Making Accommodations: The Legal World of Students with Disabilities. Bulletin of the AAUP, 87(6), 41–46. Complied Article Series (Download)

- Moynihan, M., & Bezyak, J. (n.d.). Students with disabilities in clinical and internship placements and the ADA. Rocky Mountain ADA Center. Retrieved November 5, 2024, from Guidance and Relevant Case Law

- Nott, M. L., Will, M., Llp, E., & Zafft, C. (2006). Career-Focused Experiential Education for Students with Disabilities: An Outline of the Legal Terrain. 19(1), 27–38. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Sassu, K. (2018). Access versus success: Services for Students with Disabilities in Postsecondary Education. Journal of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, 19–24. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Thomas, S. B. (2000). College Students and Disability Law. The Journal of Special Education, 33(4), 248–257. Peer-Reviewed Article

K-12 to Post-Secondary Transition

- Eckes, S. E., & Ochoa, T. A. (2005). Students with Disabilities: Transitioning from High School to Higher Education. American Secondary Education, 33(3), 6–20. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Smith, P., & Routel, C. (2009). Transition Failure: The Cultural Bias of Self-Determination and the Journey to Adulthood for People with Disabilities. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(1). Peer-Reviewed Article

Disability Culture and History

- Baynton, D. C. (2001). Disability and the Justification of Inequality in American History. In The New Disability History: American Perspectives (pp. 33–57). New York University Press. Book Chapter

- Charlton, C., James I. (1998). Nothing about Us Without Us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. University of California Press. Available at Treadway Library

- Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (Producer). (2010, August 22). The Power of 504 (full version, open caption, English and Spanish) [Video recording]. Short Documentary

- Dolmage, J. (2011). Disabled Upon Arrival: The Rhetorical Construction of Disability and Race at Ellis Island. Cultural Critique, 77, 24–69. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Fisher, J. (Director). (1996). Unforgotten: Twenty-Five Years After Willowbrook [Video recording]. Content warning: contains brief, but real, graphic footage and discussion of severe neglect of disabled children and adults Documentary

- LeBrecht, J., & Newnham, N. (Directors). (2020). Crip Camp [Documentary]. Documentary

- Madaus, J. W. (2011). The History of Disability Services in higher education. New Directions for Higher Education, 2011(154), 5–15. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Muredda, A. (2012). Fixing Language: ‘People-First’ Language, Taxonomical Prescriptivism, and the Linguistic Location of Disability. The English Languages: History, Diaspora, Culture, 3. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Nielsen, K. E. (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Beacon Press. Available through QC Iowa or Illinois library systems

- Shakespeare, T. (2010). The Social Model of Disability. In The Disability Studies Reader (5th ed., pp. 266–273). Routledge. Book Chapter

Disability Narratives

- Granger, D. (2010). A Tribute to My Dyslexic Body, As I Travel in the Form of a Ghost. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(2). Peer-Reviewed Article

- Heumann, J., & Joiner, K. (2020). Being Heumann: An Unrepentant Memoir of a Disability Rights Activist. Beacon Press. Available through QC Iowa or Illinois library systems

- Longmore, P. K. (2003). Why I burned my book and other essays on disability. Temple University Press.

- Mattlin, B. (2022). Disability Pride: Dispatches from a Post-ADA World. Beacon Press. Available at Tredway Library

- Rapp Black, E. (2016, August 31). My Paralympic Blues. The New York Times. Article

- Rodis, P., Garrod, A., & Boscardin, M. L. (Eds.). (2001). Learning Disabilities & Life Stories. Allyn & Bacon.

- Smith, P. (2013). Both Sides of the Table: Autoethnographies of Educators Learning and Teaching With/in [Dis]Ability. Peter Lang.

- Wong, A. (Ed.). (2020). Disability Visibility. Vintage Books.

- Wong, A. (2021, March 7). Disabled Students (No. 98) [Broadcast]. Podcast Episode

Inclusive Practices

- Carter, M. (2023, December 21). Person First Language and Identity First Language. disAbility Law Center of Virginia. Article

- Clem, A. (n.d.). Disability Etiquette—A Starting Guide. Disability:IN. Retrieved November 10, 2024. Infographic

- Ladau, E. (2015, July 20). Why Person-First Language Doesn’t Always Put the Person First. Maryland Coalition for Inclusive Education. Article

- Ladau, E. (2021). Demystifying Disability: What to Know, What to Say, and How to be an Ally. 10 Speed Press. Available at Tredway Library

- Perner, D. E., Laz, L., SpEd, M., Murdick, N. L., & Gartin, B. C. (2015). People-First and Competence-Oriented Language. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 11(2), 16–28. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Supporting Accommodation Requests: Guidance on Documentation Practices - AHEAD - Association on Higher Education And Disability. (n.d.). Retrieved February 23, 2024, from Professional Guidance

- West, E. A., Novak, D., & Mueller, C. (2016). Inclusive Instructional Practices Used and Their Perceived Importance by Instructors. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 29(4). Peer-Reviewed Article

UDL

- Burgstahler, S. (2021). A Framework for Inclusive Practices in Higher Education. DO-IT. Article

- Burgstahler, S. (n.d.). Equal Access: Universal Design of Instruction. DO-IT. Retrieved July 21, 2025, Article

- Dolmage, J. T. (2017). Online Resources for Academic Ableism. University of Michigan Press. Online Resource

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2013). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. Cast, Inc. Available at Tredway Library

- Mirko, C., & Novak, K. (2020). Equity by Design: Delivering on the Power and Promise of UDL. Corwin Press. Available at Tredway Library

- Rose, D. H., Harbour, W. S., Johnston, C. S., Daley, S. G., & Abarbanell, L. (2006). Universal Design for Learning in Postsecondary Education: Reflections on Principles and their Application. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 19(2), 135–151. Peer-Reviewed Article

- Campbell-Chudoba, R., Dzaman, S., Isbister, D., & Maier, J. (2025). Universal Design for Learning: One Small Step. University of Saskatchewan Open Press. Digital Book